35 Years of Innovation: The Cocalis Chronicles

Words By: Richard Cunningham

Wilbur and Orville Wright's first successful powered airplane remained aloft for only twelve seconds. The image of Flyer 1 taking flight on December 17, 1903, captured the moment that would define the 20th century, but it only tells us half the story.

The Wright’s goal was to create a reliable airplane capable of controlled, sustained flight. Their greatest gift may have been that the two bicycle makers documented every step of their creative process – a laborious series of successes, failures and improvements that began with a bright idea in 1899 and culminated in the first serial production of a two-seat airplane in 1906. It was a road map for future inventors, and it taught us that innovation and refinement are equal parts of a successful creation.

Truly innovative bike brands, those willing to commit wholeheartedly to the refining process, are rare. Creative individuals who possess the ambition to continuously revise and improve their inventions, and to respond positively to criticism – are the rarest. These people are the reason that mountain bikes are so good today – and one of those is Chris Cocalis.

Chris and I first met 36 years ago, when I was a pioneer mountain bike maker with a head full of wild ideas. It was a memorable conversation between two creative rule breakers. Our life-long friendship, however, began five years later after I retired my welding torch to become the editor of Mountain Bike Action magazine and Cocalis had founded Titus Cycles.

Now a journalist, I discovered that in addition to his creative genius, Chris had a sharp mind for business, the humility to reach out to others throughout his creative process – and an obsession for small details. Without question, this enviable skillset helped Cocalis successfully navigate three decades of chaotic innovation and changing standards to become a driving force within the industry and a world-leading mountain bike maker. It’s a story worth telling.

The Bottom Bracket

Back in 1987

a twenty-something Chris Cocalis visited me at Mantis Bicycle Company to show off his titanium bottom bracket design. With great urgency, the product engineer, assembler, sales manager and president of Snake Cycles walked me through the nuances of his invention.

We had become a regular stop for mountain-bike-industry hopefuls (big-names and no-names), either shopping a new component or searching for a second opinion on some secret project. Most often, these were one-off prototypes, so when Cocalis produced a finished product that was actually in production and sourced from local Arizona aerospace suppliers, he had my full attention.

Modern bottom brackets

Most modern bottom brackets feature external bearing cups and oversized axles, but such was not the case in the 1980's.

Back then, bearing cups threaded into the frame’s bottom bracket shell, which restricted their dimensions and undermined the strength of the assembly. Cocalis designed external cups that housed sealed, double-row ball bearings and left ample room inside the frame for a larger-diameter titanium axle. Simple, stronger, no maintenance required, and lightweight.

This was an elegant solution to one of many nagging issues that mountain bike makers inherited from legacy component manufacturers, reluctant to deviate from century-old road bike standards. I asked what motivated Cocalis to butt heads with the likes of Shimano, and attempt to convince an army of bike mechanics who were perfectly content to slather white grease on unshielded axles and chase loose ball bearings around the shop floor, to embrace his revolutionary bottom bracket?

“Mountain bike bottom brackets are all pretty much the same. After I broke three or four, rather than waste more money on crap, I made myself a better one. I figured I wasn’t the only guy out there who was trashing bottom brackets, so here I am.”

Chris thanked me for my time and as he began the 350-mile trek towards Phoenix, I had a strong sense that our paths would cross again.

The Back Story

Chris may have been a freshman mountain biker, but this wasn’t his first rodeo. Cocalis exhausted every shop class project at his Illinois high school. He graduated with a college scholarship and a pro BMX license then and made a beeline to Arizona State University to pursue business and engineering degrees…

“…Mostly so I could race a lot more. The BMX Winter Nationals were in Phoenix, and there were enough tracks that you could race just about every night of the week if you wanted.”

Cocalis chipped away at his ASU curriculum while working his way up the financial ladder from bike shop rat to store manager. Now, anyone familiar with the cycling industry knows that only drug addiction guarantees a faster downward trajectory than the career of an aspiring pro racer who works for a bicycle retailer. Somehow, Cocalis flipped that script.

Stint as a Bike Retailer

During his stint at the bike retailer, Chris managed two shops, discovered mountain bikes, abandoned BMX, met his future wife, built his first frame, met the aerospace welder with whom he would launch Titus Cycles, and switched his major to business from engineering. Before we get too far ahead, however, let’s go back to “discover mountain bikes.”

Cocalis was racing BMX at the peak of its evolution when frame and component failures were finally few and far between. Mountain bikes, however, were still in their teething stages. One could forgive Chris for assuming that a mountain bike would be at least as durable as his BMX machines.

As the story goes, a local kid rode his new Schwinn High Sierra out to the local dirt jumps. Cocalis asked him if he could try it. Chris’ initiation to the sport lasted less than a minute. After hitting a few berms, he hit a “reasonably sized jump” and destroyed the frame leaving a less than positive impression of the sport of mountain biking. Cocalis doesn’t handle disappointment well, so it came as a surprise that he would ever ride a mountain bike again. But he did…

“When I get into something, I tend to become a bit obsessed with it. Once I went on my first real mountain bike ride, I was hooked for life.”

Chris, the Bike Builder

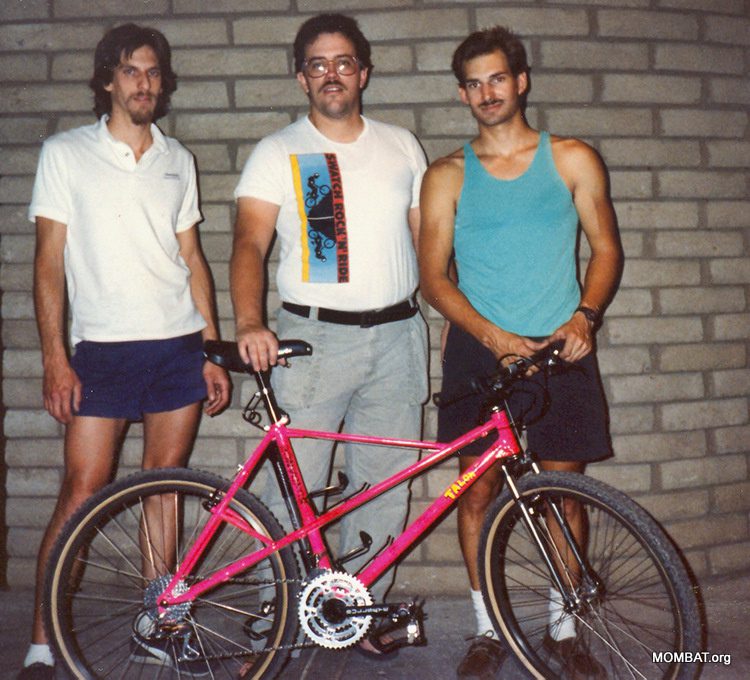

The next time Mr. Cocalis crossed my path was when the editors of Mountain Bike Action magazine brought a pickup truckload of bikes to Mantis for a round-table discussion. MBA was working on an October 1989 feature story titled: “Fast Bikes of the Future.” One of the most exotic designs in the mix was the Sun Eagle Bicycle Works Talon Elite, an elevated chainstay, twin X-tube frame with a crazy red, white and blue paint job – designed by Chris and constructed by him and his partner, Alan Vaughn. No surprise that the Talon’s deviation from the traditional “double-diamond” frame was a workaround to eliminate a number of glaring issues that the industry at large was either unable or unwilling to address. Cocalis explained his frustrations:

“Existing sprocket designs caused “chain suck.” Climbing in the small or middle chainrings, or often while shifting the chain would bind against the sprocket teeth and “suck” up against the right chainstay. That was a big problem. Also, narrow bottom brackets and the crank designs of the time cramped rear tire clearance, which forced everyone to adopt longer-than-optimal chainstays and we really liked super short chainstays back then. Elevated chainstays pretty much eliminated those issues. Plus, they looked really cool.”

In spite of their five minutes of fame in MBA's feature story, only a dozen Talon Elites made it to production.

Both Cocalis and Alan had day jobs, so welding up Talons in Alan’s backyard occupied most of their evenings and weekends. Not a sustainable business model, but even so, other forces were at work that would lead Cocalis in a different direction.

Rockshox suspension forks, along with an army of small innovative component makers, sparked a revolution in the 1990s that would force legacy component makers to quickly solve the shortfalls that their innovative Talon Elite once addressed. The inevitable demise of elevated chainstay designs also marked the end of their partnership, but it wouldn’t be long before Cocalis was back in the garage, burning the midnight oil in the quest to build the “ultimate mountain bike.”

The Beginning of Titus

“I was working at the bike shop when this random guy walked in waving a mountain bike magazine. He was angry about an article that described how difficult titanium was to machine and weld. Turned out that Mark Zepeda was a welder at an aerospace company in Phoenix who knew nothing about bikes, but a lot about titanium. Zepeda came up with the name, “Titus” and we started making titanium stems and bar-ends in his garage. Next, we made some fixtures to build frames. We would build a frame, and then sell a frame. I think we had only built 3-4 frames when I met John Rader (the guy who invented the threadless headset) at a bike race.”

John had spoken with Chris about a novel rear suspension he had designed. Cocalis offered to build some prototypes but did not expect their conversation to bear fruit. They built several prototypes for John Rader who used these initial examples to sell the design to Univega, a valued brand of that period.

Surprisingly, Cocalis received a purchase order to produce 175 “Shockblok” titanium full suspension frames for the brand’s new high-end mountain bike line. It was a daunting proposition. Cocalis admitted that the best the pair could manage was one frame a month. He was a senior, finishing up a degree in accounting, and was plying Fortune 500 firms for a desk job and a decent salary – and now this? Cocalis put together a business plan and then discussed his dilemma with his trusted mentor Hal Reneau, an accounting professor at Arizona State University. “Do it,” he said. “This is a once in a lifetime opportunity. You can become an accountant anytime you want.” He then backed up his advice with a small loan to help Chris to get started.

“Mark’s boss, Larry Richmond, also threw in some money. We had just enough to rent a building, buy materials, a milling machine, a lathe and some TIG welders. Once we got going, we hired some of Mark’s swing shift co-workers to help us deliver the frames on time. I coped [cut and fit] every tube for that entire production run.”

Titus Cycles delivered the 175 frames to Univega as promised, but never received a follow-up order. The next move should have been to go into production with a name-brand Titus range, but Cocalis decided upon a more conservative business plan. They “soft launched” Titus frames to build up their name and contracted to build frames in greater numbers for more established brands to maintain their cash flow.

“We made aluminum suspension downhill frames for the Diamondback team; titanium frames for Dean, Slingshot, Conejo, Hammerhead, and Speedgoat; rear triangles for Sycip; all the custom titanium road bike frames for the Lemond team, and even some titanium steerer tubes for Kestral.”

Cocalis says that it wasn’t until 1996 that they really focused on Titus as their stand-alone business. By that time, Titus had produced frames from aluminum, titanium, steel and metal matrix – and had manufactured at least four different types of rear suspension designs. In retrospect, the experience must have been a postgraduate course in production frame building for Titus – which spurred an incredible period of innovation that would earn a place in history for the Titus brand.

Dual Suspension VS Chris Cocalis

Titus produced a number of stunning titanium hardtails, many of which are still on the trail or in private collections, but as the 90s rolled in, just about everyone who cared about expensive hardtails, titanium or otherwise, already owned two. Most of the cross-country community (at least in the US) were avid trail riders, not racers. These new school riders worried less about how much their mountain bikes weighed and more about how capable they were. This subtle shift in consciousness was the green light Cocalis had been waiting for to commit to full suspension. Cocalis was ready, but the bicycle industry was not.

If I were asked to choose one person to spearhead the development of the dual-suspension trail bike, it would have been Chris. He is one of the best technical trail riders I’ve known on a mountain bike – and on a motorcycle, he earned a reputation for slaying nationally ranked off-road riders in his Arizona desert playgrounds. So, here’s a guy who understood suspension, a perfectionist who had been manufacturing world-class mountain bikes, who had serious riding skills and who had this elegant vision of what a dual-suspension mountain bike could become. Cocalis, it seemed, possessed all of the necessary elements to bring that vision to fruition. What he didn’t have, however, was control over the supply chain that furnished suspension components. If there were such a thing at the time.

Cocalis the perfectionist

Cocalis the perfectionist had total control over Titus’ rigid frame manufacturing. Get the tube sizes, the alignment, and the geometry right, and a hardtail frame is done. After welding, it’s one simple part designed to fit a whole bunch of off-the-shelf components that were someone else’s responsibility. Adding rear suspension to that equation, however, created a multitude of manufacturing and sourcing issues, most of which fell outside the cycling industry’s wheelhouse. This time around, Cocalis’ success would depend largely upon sourcing reliable partners who shared his vision.

This was a paradigm shift for Cocalis, and he owned it. Today it’s safe to say that every major component maker in the world has a story to tell about Chris and his dogged quest to improve and perfect the interface between his bicycles and their products. He could sense the slightest deviation in a fork or shock tune. He pushed for disc brakes, wider axle spacing, perfect chainlines, through-axles, direct-mount derailleurs and he celebrated his victories one millimeter at a time. In his words:

“I think that most of our vendors would say that I am extremely tough and expect a lot, just as our customers expect from us. They would also say that we have brought positive changes to their capabilities and processes. I expect achievable perfection and push them hard to be better – very often, we show them how to get there.”

His first stop was AMP Research.

Cocalis was introduced to AMP Research founder Horst Leitner by AMP’s new product manager – the same guy who gave Titus the Univega ShockBlok contract. Cocalis went home with an AMP rear suspension and an agreement from AMP to purchase more in the future. The progeny of that meetup would eventually become the Racer-X, the best-selling model in the history of Titus cycles, but there was a problem.

“AMP’s rear suspensions were not aligned properly. When I confronted Horst, he blew me off like I was some young guy who didn’t know what he was talking about.”

Cocalis made his own welding fixtures, fabricated a few copies of AMP’s swingarm and strut, then drove back to Laguna Beach, California, to take Horst and company to task. Horst was livid, but eventually, he cooled off and Titus’ relationship with AMP was quickly mended. Shortly after, Titus developed their own, more robust versions of the Horst Link under a modest royalty agreement that Horst protected in writing when he later sold the patent to Specialized. Horst would later say that Chris was the first bike maker to license his patent and the only one who paid his royalties.

Adopting the Horst Link design turned out to be a brilliant move for Cocalis,

as witnessed by the fact that the same four-bar configuration is still popular today. With the addition of a secondary linkage, Cocalis achieved the rigidity he desired and the ability to adopt a broader range of shocks and leverage rates.

Armed with a proper rear suspension, the next challenge was to convince the likes of RockShox and Manitou that aggressive trail riders were becoming the new normal. Their race-oriented mindset, however, divided the sport between spindly lightweight cross-country, and pendulous downhill bikes. Between those extremes was a barren desert of opportunity that Cocalis intended to populate with uber-capable dual suspension trail bikes – but he couldn’t get there without more sophisticated damping and longer-travel forks. Getting RockShox and Manitou on board, however, was not going to be easy.

Enduro Before Enduro

Titus’ Racer X became an overnight success because it only had 60 millimeters of travel, and it looked and rode much like a conventional cross-country bike (only better). Cocalis, however, had bigger plans. Titus entered gravity racing in 1998 with the debut of the Quasi-Moto – a radical looking aluminum downhill chassis with a bolt-on subframe that was built around a new remote-reservoir coil-over shock from Fox. That same year, Cocalis released an air-sprung lighter and more pedal friendly version that challenged the very definition of the mountain bike.

When Cocalis launched his Moto-Lite, it was the prototypical long-travel trail bike. Exactly what riders needed to take the sport to the next level – before most realized they actually needed it. The Moto-Lite’s chassis was a complete departure from the modified double-diamond Racer X. Its alien-looking frame profile traced the locations of hard points where the swingarm and shock linkage intersected. Its seat-mast subframe provided stand-over clearance for an “unheard of” 125 millimeters of wheel travel. It was ahead of its time in more ways than one.

Titus sold a lot of Moto-Lites

Chris says Titus sold a lot of Moto-Lites, predominantly to riders in Arizona, Colorado and Utah where the most technical trails were concentrated. No surprise there, it was forged into existence on the boulder fields of South Mountain. In Southern California, however, where most of my test riding began with a big chunk of fire road climbing, the Moto-Lite required a positive, winning attitude to overcome its lackluster feel at the pedals. Some of that could be attributed to the “long-travel learning curve” that today’s riders have mastered, but truth be told, there were no shock or fork options back then that fit the Moto-Lite’s intended role.

The Moto-Lite debuted when the longest travel fork in the RockShox lineup was their 80mm travel dual-crown Judy DH. Marzocchi had just developed its single-crown 100mm travel Bomber Z1 and Manitou was struggling to keep up. Cocalis opted for a limited production 150mm White Brothers dual-crown fork (which, ironically, was also the lightest option in the 100mm plus category), and a Fox ALPS air-sprung shock. Good, but not optimal choices.

The lightweight, long-travel single-crown fork, and the consistent-feeling air shock with a pedal-friendly compression damping lever that Cocalis needed to perfect his creation, were still two years over the horizon. For the moment, Chris had outpaced suspension development – a lesson learned that would shape the second chapter of his career.

The Big Picture

When Cocalis founded Titus he was 21 years old and had a hand in almost every aspect of the business. In the following decade, he had successfully steered Titus through the dual-suspension revolution and his modest production line was at full capacity producing frames that, in this man’s opinion, were unrivaled in both quality and technology. Titus was at a turning point.

After a couple of attempts to outsource frame construction to contractors in the USA, Chris successfully moved some of his aluminum models to Kinesis – a Taiwan owned builder in Portland, Oregon. To control the experiment, Titus manufactured the same bikes while Cocalis was helping the Portland factory get up to speed…

“We… started production in-house while working with Kinesis on the same model. This, combined with my previous learning experience, helped to make this a really successful project for us, and almost doubled the size of Titus that year.

Kinesis Taiwan then chose to shut down Kinesis USA and we had the option of pulling the project back in-house or transferring the project to Taiwan. We transferred it to Taiwan and this was really when Taiwan became my second home.”

Being separated from Titus for weeks at a time required some fundamental changes. Knowing Chris, I consider it a small miracle that this type-A creative genius, control freak managed to step out of his hands-on management role and seamlessly delegate the lion’s share of his skillsets to trusted employees – many of whom are still working with Cocalis today.

Stepping back from the minutia of the factory floor, and frequent travel to factories in Asia, afforded an opportunity for Chris to view Titus and the industry from a wider perspective. Perhaps more importantly, he gained access to new components and proposed standards much earlier in their development process.

Our trailside conversations changed dramatically from how a bike rides – frame geometry, suspension kinematics and handling issues – to discussions about future technology, like carbon vs aluminum, optimal tubing shapes, though-axle diameters, internal headset standards, how many cogs could fit on a cassette before we’ll need wider hubs, 29 inch wheels, and a slew of hydraulic disc brake woes. I would learn later that Chris was working on most of those issues in secret.

It didn’t take long for Cocalis to earn a place at the table when the industry’s key players were still in the planning stages. Whether this was intentional or not, Titus was poised to stay abreast of developing technology at the brink of the new millennium, which would see almost every mountain bike convention upended.

Unexpected Turn of Events

Titus did not end well for Cocalis. He had co-developed a process to fine-tune the feel of his high-end road and cross-country frames using layers of carbon fiber molded into perforated laser-cut titanium tubes. “Exogrid” tubes were manufactured by an aerospace firm called Vyatek. The ends were left bare, so they could be fitted and welded in conventional frame fixtures. The end result was stunning to look at and, according to Cocalis:

“Exogrid created a ride that probably couldn’t be duplicated with any other material, but we couldn’t have invented a more expensive process to build a frame.”

In 2001, the two companies merged with the plan of leveraging Vyatek’s manufacturing and financial resources to increase Titus’ high-end production in the USA. Five years later, their relationship unraveled and Cocalis parted ways. It was a dark moment and a blessing in disguise.

In the years leading to the merger, Chris had learned the ropes of offshore production and cemented close ties with key OEM component suppliers. He felt he had squeezed all he could from the Horst Link suspension and was already considering a new direction. Exactly one year later, when his non-compete clause expired, Cocalis founded Pivot Cycles. I was not surprised.

Starting Over

For Cocalis, Pivot Cycles was a clean slate, a chance to consolidate his hand-picked successors and critical partnerships under his new banner and to put together a well-funded global business model that could be managed close to home. Cocalis said that it only took a few phone calls to lock down his investors, some of which helped him found Titus. He struck a suspension deal with Dave Weagle, and one year after he left Titus, all of the pieces were firmly in place. Pivot Cycles launched two aluminum dw-link models, the Mach 4 and Mach 5 by Summer of 2007.

“That first Mach 4 and Mach 5 featured technologies, innovation and integration that had never been seen before. We took a look at the bike as one unit and not just a frame that you bolted a group kit to. Within just a couple model years, everything changed with everyone’s bikes. It spurred the next level of innovation.”

They’ve got a busload of carbon mountain bikes for sale, engineers in the US, an operation in Germany, assemblers in Europe, factories in Taiwan and Southeast Asia, and a relatively new headquarters that’s only a ten-minute ride to the South Mountain trailhead in Tempe, Arizona.

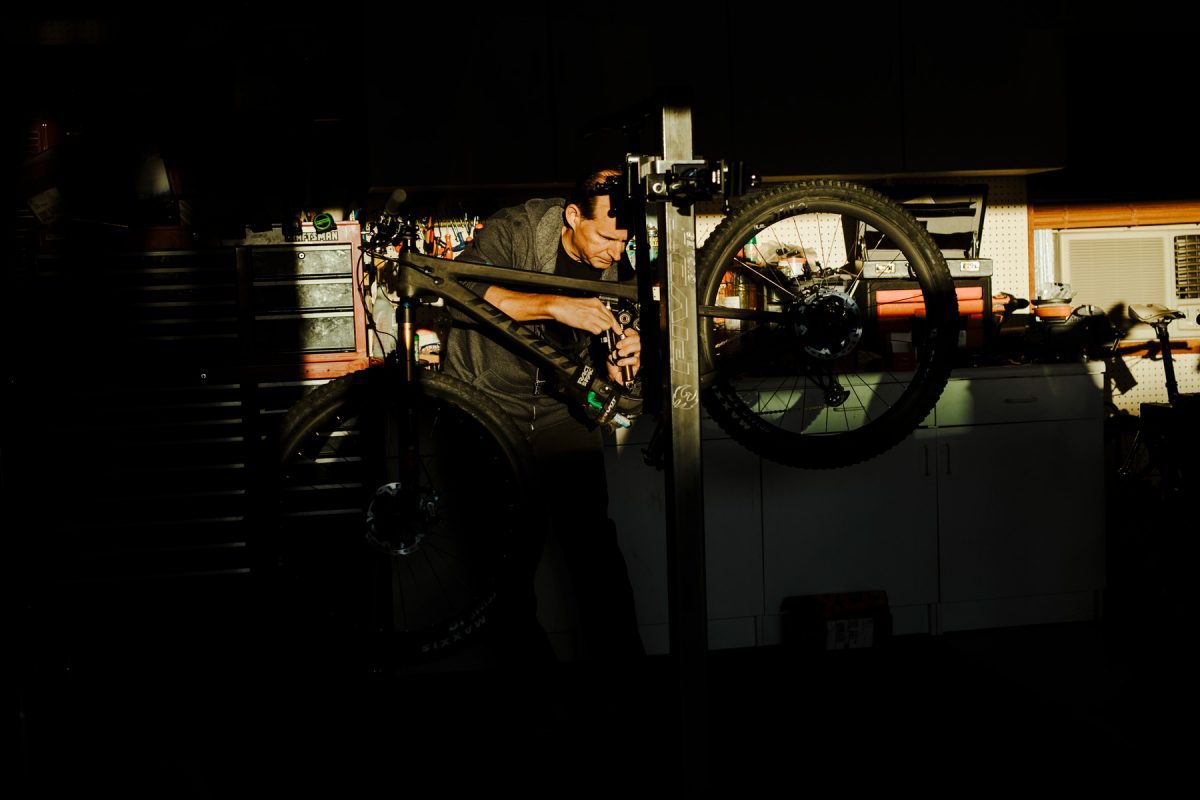

16 years later

16 years later, the vibe feels the same as it did when Pivot Cycles was just Chris and Cindy Cocalis in the office, an in-house sales staff, four guys assembling bikes, and Bill Kibler hiding behind an array of CNC machines in the back of the warehouse. And Chris still makes bikes in the USA. Pivot builds prototypes and test mules for every new model in their Tempe headquarters, in both aluminum and carbon fiber – to make sure everyone is on the same page.

I’ve been told that if a CEO is doing his job, nothing ever happens. Employees get paid, bikes arrive and get shipped, there’s always a surplus to cover an emergency and they turn a profit. That’s how Chris has always done it.

It's hard to believe that it's been over three decades since I first met Chris and that I've ridden every significant mountain bike he's produced in the last 30 years. And Chris? We still make time to ride together at least twice a year and he still kicks my ass. We geek out on mountain bike stuff, and I can honestly say I've never seen him happier.

I was inspired to write this story while riding a prototype of the 2024 Switchblade near my home in Colorado. Once, I solemnly swore that my previous Switchblade was the perfect trail bike. In five years, it’s never let me down – not one component failure or a single flat tire. Today I caught myself uttering that same sentence about this new machine. Is “perfecter” an acceptable superlative?

Incredibly, I had aced a nasty technical rock feature for the first time this Summer. Recovering at the summit I took pause to admire the finer details of my new Pivot. My thoughts drifted to an earlier time when bikes rattled, when I brought tools to fix every moving part, when chains fell off and brakes faded, when suspension damping changed with intensity and temperature, when I checked my frame for cracks before each ride, when I thought, “this was the best bike ever.”

Beneath the Switchblade’s sparkling paint was the DNA of the Titus Moto Lite, and between them, a thousand layers of innovations and meticulous improvements. I realized that the man responsible for this carbon fiber and metal masterpiece also played a significant role in the refinement of almost every one of its components. Chris could have abandoned his quest to perfect his trail bike at a number of points along that timeline and called it good enough, but he never did.

I dropped my saddle, pointed the front tire downhill, released the brake levers and felt my left shoe click into the pedal, and in that moment of weightlessness before gravity sent us reeling toward home, I thought, “This is a story worth telling.”